Alumni Spotlight: Monica Alejandra Noriega

“I had some great clinicians growing up, but I never had an experience of feeling fully seen by my clinician,” shared Wright Institute Clinical Psychology Program graduate Monica Noriega. “It didn’t allow me and my family to grapple with how legacies of violence impact how we view ourselves, others, and the world, and more specifically how we process our emotions with our children.”

“I had some great clinicians growing up, but I never had an experience of feeling fully seen by my clinician,” shared Wright Institute Clinical Psychology Program graduate Monica Noriega. “It didn’t allow me and my family to grapple with how legacies of violence impact how we view ourselves, others, and the world, and more specifically how we process our emotions with our children.”

Monica grew up with her parents and siblings in Salinas, California. The granddaughter of migrant farm workers from Mexico, she was raised in a diverse, largely Latine community where she had more privilege than many due to her parents’ education and citizenship status. During her childhood and teenage years, Monica witnessed a lot of violence in her community. “That really inspired my trajectory to work with the Latine community and work specifically with trauma and intergenerational trauma,” she explained. “I saw that, in our communities, when brown kids got shot or were killed by police, there was no sort of public outcry, but our community had our own rituals, our own ways of grieving and our own ways of celebrating each other.”

From a young age, Monica was aware of the need for diversity among mental health clinicians. “I had my own experiences with trauma growing up for which I was very fortunate to get mental health services, but none of those services ever accounted for my Chicanx identity, our intergenerational wisdom, or the impact of colonial violence on how much access we have to our ancestral wisdom as Chicanos,” she reflected. “Harnessing our collective power was always seen as something separate from the therapeutic space.” As she headed off to college, it was clear that she sought to change the way things had always been.

For her undergraduate studies, Monica attended Santa Clara University. At first, she planned to major in public health, but it didn’t feel like the right fit. When she first discovered psychology, she had mixed feelings about it. Although the topic interested her, it felt “very white” and she didn’t see herself in the coursework. “It was really through the marriage of psychology with ethnic studies that I found the why: why do our communities experience these higher levels of violence?” she shared. “Being able to trace those roots back to colonialism and white supremacy culture and integrating that with what I was learning about attachment in early childhood and the importance of the parent child relationship is what inspired me to go into early childhood trauma work.” In 2014, she graduated with a double major in Psychology and Ethnic Studies.

From 2013-2015, Monica was a Behavioral Therapist at Gateway Learning Group in San Francisco, working with children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. “I learned a lot through that experience, but it’s also what really inspired me to get my doctorate,” she explained. “I was the only Spanish-speaking behavioral therapist, so I was with all the Spanish speaking families, but I never had a Spanish-speaking supervisor and I never had materials in Spanish.” Because this was one of few jobs in the field that she was qualified for without a masters or doctoral degree, Monica realized she needed to continue her education. “I wanted to learn how to be a clinician, but I also wanted to get a seat at the tables where decisions are being made about whose communities get more access to resources, what kind of resources, and for what reason,” she reflected.

In 2015, Monica enrolled in the Clinical Psychology Program at the Wright Institute. She chose to pursue a PsyD and not a masters degree because of her interest in assessment. “I'm really passionate about early childhood work, but I also wanted the skills to be able to collaborate with families and help them see their children more fully,” she explained. “And see themselves in this work as well in a way that feels not just culturally relevant, but sort of culturally-grounded, that we're doing this together, not from a space of the white gaze perpetuating or projecting pathology onto brown children.” Monica graduated with her PsyD in Clinical Psychology in 2020.

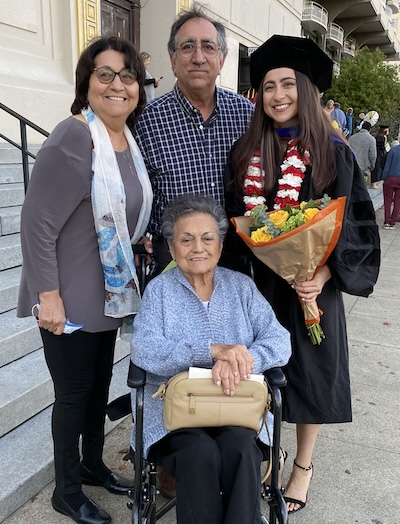

Monica’s happiest memory from her time at the Wright Institute was being chosen as the keynote speaker for her graduation ceremony. “I'll never forget seeing my 93-year-old grandmother in the audience,” she recalled. “Her hearing me speak so boldly and unapologetically about liberation and about our people, and me being one of only two Latine students in our whole cohort, that was probably my proudest moment.” Her biggest challenge came after graduation when the Wright Institute ended their Sanctuary Project, which was one of the things that brought her to the Wright. “I've always been passionate about migrant justice and integrating liberation work with my clinical repertoire and my professional identity,” Monica reflected. “There were no other doctoral level programs that were training clinicians to do psychological evaluations for asylum seekers with asylum seeking populations from Central America - it was an incredible program.” After it ended, she felt disappointed, but understands that funding is challenging and changes over time, noting that she is “hopeful that someday soon we will be able to reinvest in where our values really are.”

Monica’s happiest memory from her time at the Wright Institute was being chosen as the keynote speaker for her graduation ceremony. “I'll never forget seeing my 93-year-old grandmother in the audience,” she recalled. “Her hearing me speak so boldly and unapologetically about liberation and about our people, and me being one of only two Latine students in our whole cohort, that was probably my proudest moment.” Her biggest challenge came after graduation when the Wright Institute ended their Sanctuary Project, which was one of the things that brought her to the Wright. “I've always been passionate about migrant justice and integrating liberation work with my clinical repertoire and my professional identity,” Monica reflected. “There were no other doctoral level programs that were training clinicians to do psychological evaluations for asylum seekers with asylum seeking populations from Central America - it was an incredible program.” After it ended, she felt disappointed, but understands that funding is challenging and changes over time, noting that she is “hopeful that someday soon we will be able to reinvest in where our values really are.”

During her time at the Wright Institute, there were two professors who had a big impact on Monica: Dr. Anatasia Kim and Intervention: Family Systems and Multicultural Awareness classes, then became her dissertation chair. “Her classes had a huge impact on me, but it was more than that,” she explained. “Her mentorship and her leadership, how she modeled being a woman of color, a scholar, and a clinician, and her fierceness allowed me to step into my power a little more.” She also enjoyed the psychodynamic psychoanalytic training she got from Dr. Barrows in her Intervention: Child and Adolescent Treatment course.

For her internship, Monica was a Pre-Doctoral Psychology Intern at Providence Saint John’s Health Center, working in their Child and Family Development Center in Santa Monica. In that role, she provided therapy and conducted assessments with children and adolescents in English and Spanish. She was halfway through her internship when the pandemic began and turned everything upside down. “It was a huge lesson in the inequities and inequalities that exist in our field and in the world that were amplified at that time, especially on the backs of undocumented children and families and the people who serve them,” she recalled. “I learned a lot about listening to myself, trusting my intuition, stepping into my power, and also about how to navigate collective trauma.” She still uses the skills she learned at her internship during the pandemic in her work today as a consultant. “It's different being a provider that is of the same community you’re serving and seeing people go through these specific traumas and forms of systemic oppression that you yourself are also being confronted with, possibly to a lesser degree,” she explained. “That inspired my trajectory as a trainer and someone who develops curriculum about these things to help other organizations that do front line work with highly traumatized populations.”

The title of Monica’s dissertation was “Trauma and Resilience among Latinx Girls: A Mixed Methods Exploration of Positive Adaptations for Trauma and Healing (PATH).” She knew she wanted to do her dissertation on trauma among Latina youth and thankfully an opportunity presented itself during her practicum at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland. One of her supervisors, Dr. David Hoskins, developed an “evidence-based multi-family group treatment modality for parent-child dyads with adolescents who had experienced trauma” and Monica led those groups for two years. “I took it as sort of an opportunity to not just deepen my clinical skills, but also to contribute something to the field around not just how we heal from trauma in the parent-child relationship, but how we heal from trauma as a community and how our communities heal from trauma together,” she shared. “My findings were that multi-family group therapy for Latina adolescent girls is effective in reducing PTSD, not just in the youth themselves, but also in their caregivers.”

Monica learned a lot of valuable lessons in graduate school, but one stands out above the rest. “I learned the importance of investing in yourself as a clinician, as a scholar, and especially as a scholar activist because we can only take our patients as far as we’ve been,” she reflected. “I learned not just what I'm capable of in terms of what I can provide to the community, but also what I'm capable of in terms of providing for myself, which is just as if not more important than the work we do out in the world.” Monica also learned the importance of investing in relationships, both personal and professional, which both anchor her and serve as her driving force.

At the end of her studies, Monica felt prepared to begin her work as a clinician. “I have a really strong foundation in different theoretical modalities,” she explained. “I remember being the most confident clinician at my internship, when a lot of people from other programs were very green.” Not only was she academically prepared, she had also learned the importance of being a lifelong learner and keeping up with cutting edge research in the field. “The Wright prepared me in terms of networking as well,” she added. “Having the wide reach that they do in the Bay Area and beyond allowed me to set really strong roots in relationships and my network here and that has allowed me to have a running start to my career.” Monica also learned how to work in community and build community as a clinician and the importance of doing both during her time at the Wright Institute.

Looking back, Monica’s advice for current or prospective Wright Institute Clinical Psychology Program students is “it gets harder, but you get stronger.” The work is hard, but you’re continually learning new theories and techniques. “The world doesn’t stop harming, the globe doesn’t stop turning, but we get stronger,” she reflected. “We also acquire more skills and so do the people that we serve, so trust the people and trust yourself.”

After graduating from the Wright Institute, Monica became a Postdoctoral Fellow at UCSF’s Child Trauma Research Program (CTRP), where she provided therapy and consultation to parents and children. “I did Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP), working explicitly towards interrupting cycles of intergenerational trauma during pregnancy and in the first five years of life,” she explained. “Doing that work with my now mentors, Drs. Alicia Lieberman and Gloria Castro, and getting that in-depth learning has been invaluable.” This postdoctoral position also allowed Monica to find her own voice and power as a clinician with something different to offer.

In September 2022, Monica added the role of Clinical Supervisor at UCSF, providing supervision to clinical and counseling psychology interns and fellows. She really enjoys being a supervisor, noting that it helps her deepen her own knowledge and challenges her to keep learning. “The supervisory relationship can be a site of revolutionary praxis, especially working with BIPOC and first generation students who are leading the charge in revolutionizing our field and pushing us to be better and do better,” she reflected. “So it’s an honor to be able to hold them and accompany them in that journey, in providing the supervisory container for them to find their voices just like I'm in the process of finding mine.”

Last January, Monica started in the role of Assistant Clinical Professor at UCSF in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Child Trauma Research Program (CTRP). “I teach a lot of seminars and didactics to our interns, postdocs, and psychiatry fellows,” she explained. “I also develop and disseminate curriculum around collective and complex trauma to early childhood providers around the country.” The topics of Monica’s seminars include perinatal trauma, migrant justice, liberation psychology, Child-Parent Psychotherapy, asylum evaluations, and PTSD and how it manifests in early childhood.

Outside of her official roles at UCSF, Monica also volunteers with the Sidewalk School (a humanitarian aid organization at the U.S./Mexico Border in Brownsville, Texas) and at the UCSF Health and Human Rights Initiative as a Pediatric Evaluator for asylum seekers. She has been heavily involved in migrant justice work since starting graduate school, noting that she used to believe she was limited in how much she could do for her community in her professional role and that much of the work had to be done outside of the clinical frame. “As an early career professional, I'm challenging that split that I thought that I had to conform to early on,” she shared. “I'm trying to find ways to integrate my values as someone that cares about women, immigrants, young children, and community, with the new power that I have as an academic, as a professional, and as a licensed clinical psychologist.” For that reason, she continually seeks out volunteer opportunities. To her peers, Monica’s message is: “It's necessary that psychologists, across our professional trajectories, not just make time for volunteer work, but really embody our values as clinicians to society.”

Despite her busy work and volunteer schedule, Monica makes sure to still set aside some time for herself. “I’m growing my spiritual practice,” she explained. “I’m also trying to deepen my relationship with traditional forms of medicine that our people have used for generations to support postpartum people and to connect more deeply with our roots, our ancestors, and with one another.” Monica has a Peruvian Inca Orchid dog named Cocomama who she loves to take on nature walks. “They're very special dogs because they are the only dogs that are indigenous to these continents of the Americas, so all of the others are colonizers,” she quipped. “The Mexica people believe that these dogs are our guardians in life and, when we die, they cross us over into the afterlife. They're also great cuddlers and very warm.” Monica also loves cooking and spent her holidays making pozoles and soups for her loved ones. “I’ve been trying to get into my señora era,” she laughed. “I like to say I’m a señora in training!”

Despite her busy work and volunteer schedule, Monica makes sure to still set aside some time for herself. “I’m growing my spiritual practice,” she explained. “I’m also trying to deepen my relationship with traditional forms of medicine that our people have used for generations to support postpartum people and to connect more deeply with our roots, our ancestors, and with one another.” Monica has a Peruvian Inca Orchid dog named Cocomama who she loves to take on nature walks. “They're very special dogs because they are the only dogs that are indigenous to these continents of the Americas, so all of the others are colonizers,” she quipped. “The Mexica people believe that these dogs are our guardians in life and, when we die, they cross us over into the afterlife. They're also great cuddlers and very warm.” Monica also loves cooking and spent her holidays making pozoles and soups for her loved ones. “I’ve been trying to get into my señora era,” she laughed. “I like to say I’m a señora in training!”

Looking to the future, Monica plans to continue working in the UCSF system. She hopes to advance to the position of associate professor, then continue to climb the ladder. On a larger scale, her hope is to secure funding in the next five to ten years for her work at the border. “I would love to secure funding in order to continue providing support for pregnant people and people with young children down there and the folks that work on the ground there every day at the shelter who support them,” she explained. “I'm already in talks with folks at UCSF that are interested in that work as well.” With her determination and passion, it’s clear that Monica will make a big impact over the course of her career.